7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

Mains: GS I – Indian society

Why in News?

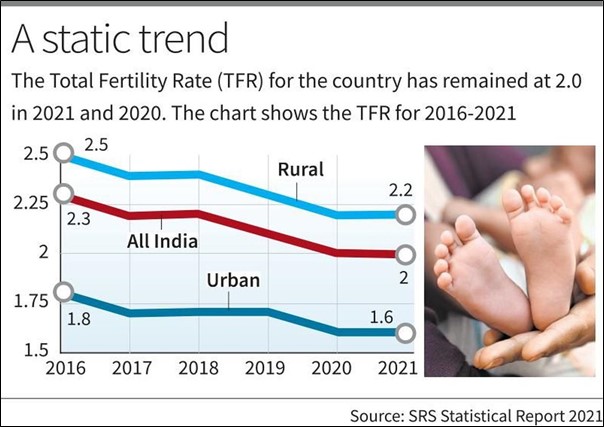

Recently, there is a large gap between real and calculated Total Fertility Rate (TFR) is particularly relevant in a developing country such as India

What is the recent UN report?

What is the perceived meaning of TFR?

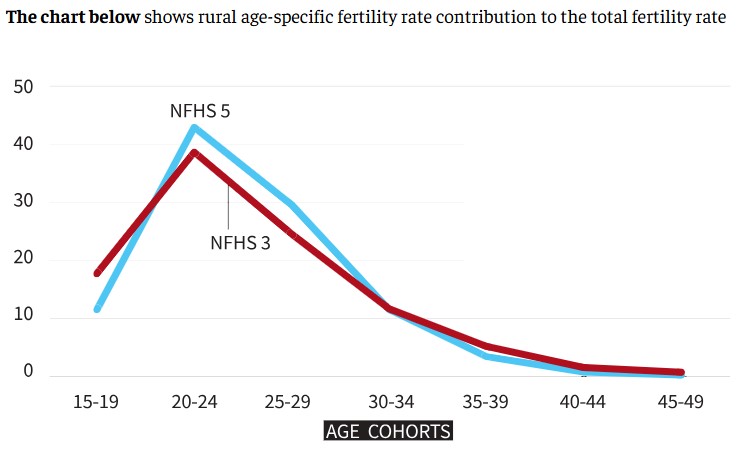

A cohort is a group of people who share a common characteristic, like age or birth year.

What are the limitations of TFR calculation?

What lies ahead?

Reference

The Hindu| Total Fertility Rate of India