7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

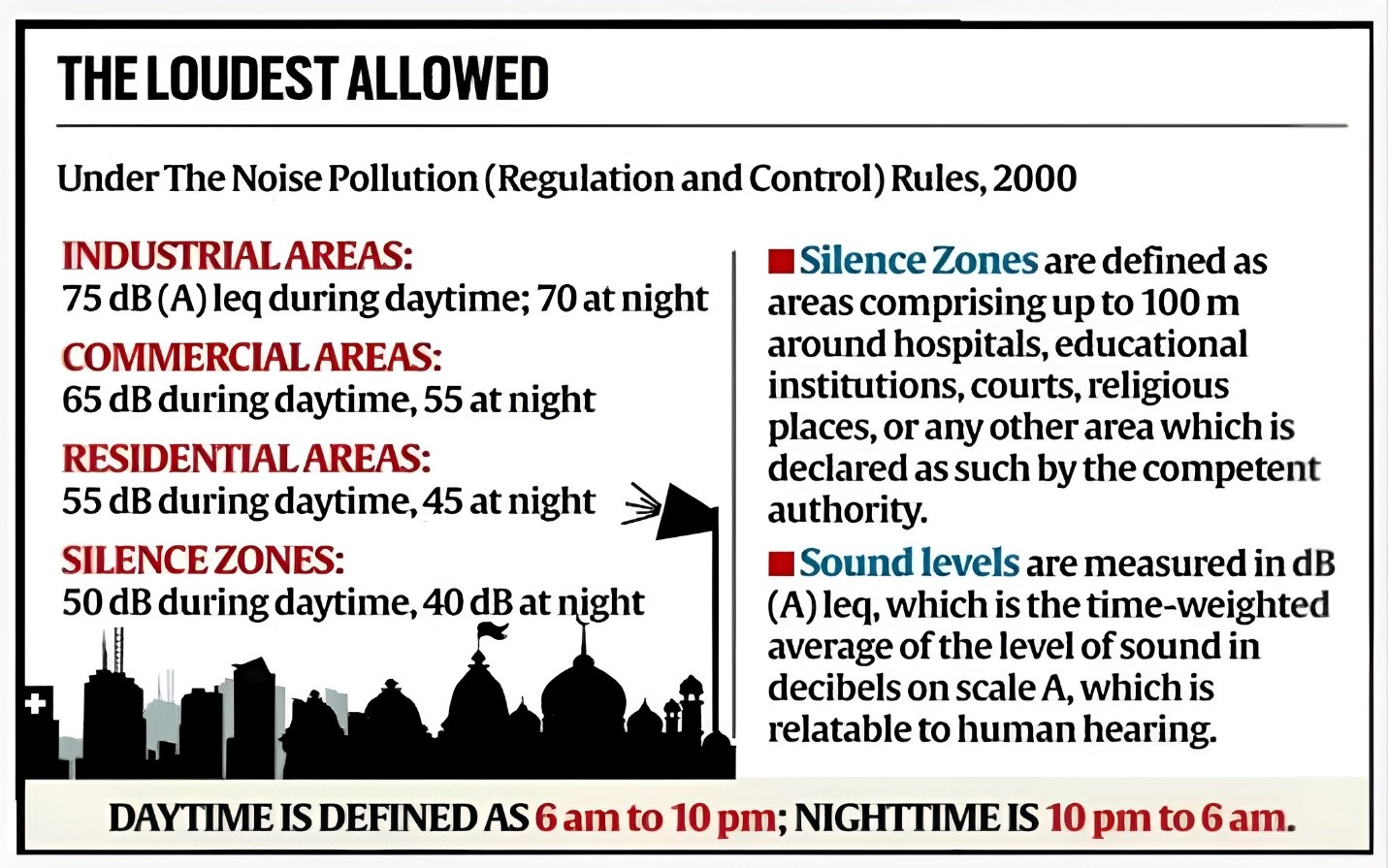

The noise pollution is one of the health hazard that has crept up unacknowledged on Indian cities.

The Indian Express| Noise pollution