7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

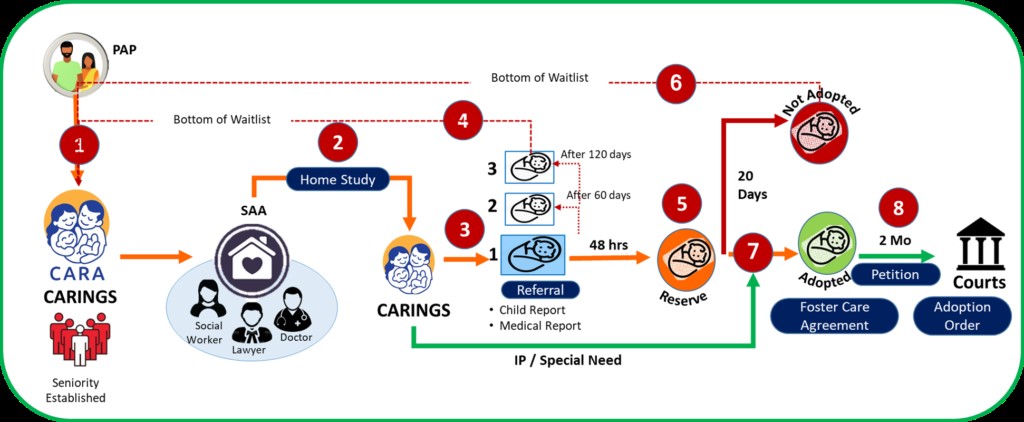

The Supreme Court has expressed concern over the delay in India’s system of child adoption.

CARA became a signatory to the Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation of 1993 and India ratified the convention in 2003.

References