7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

Mains: GS III – Disaster Management

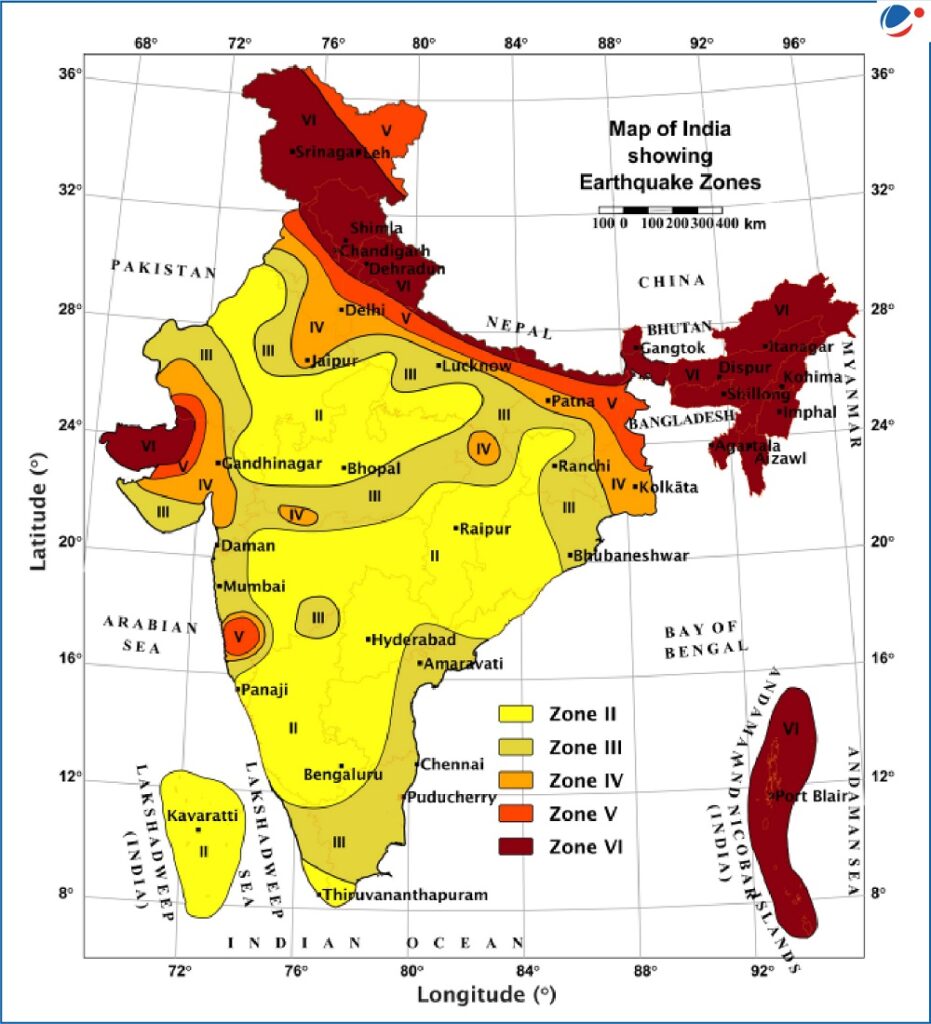

Recently, India has unveiled an updated seismic zonation map as part of the revised Earthquake Design Code by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS).

The Indian Express| New Seismic Map of India