7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

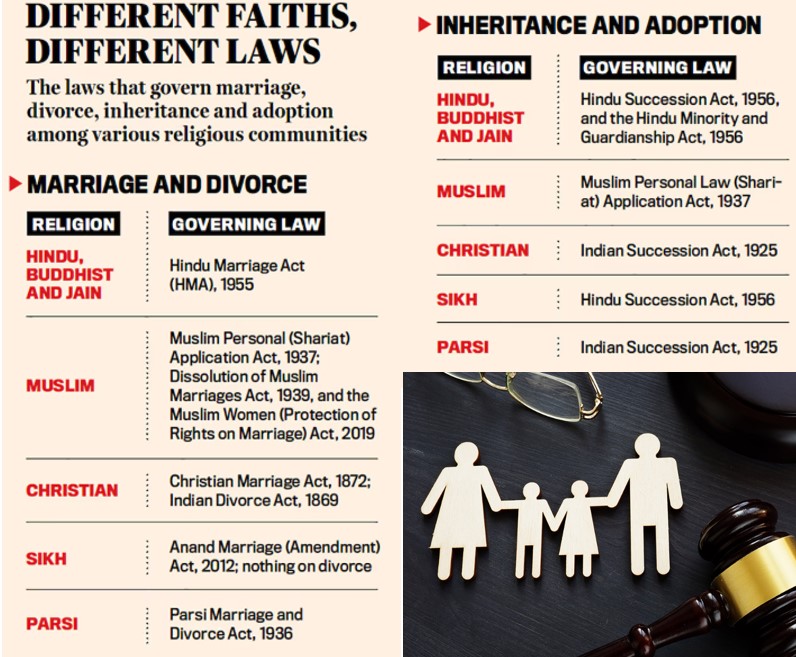

Mains: GS I – Salient features of Indian Society

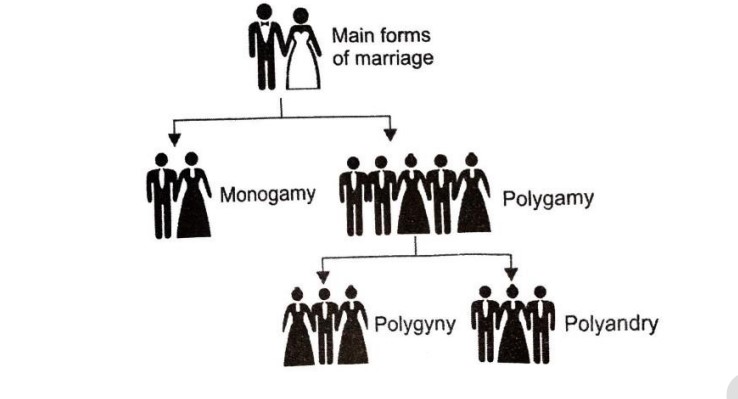

Over the years, there have been significant changes in marriage and maintenance laws.

Sambandham is a form of visiting relationship with the husband without involving cohabitation.