Why in news?

The International Labour Organisation recently released the Global Wage Report 2018/19.

What are the highlights?

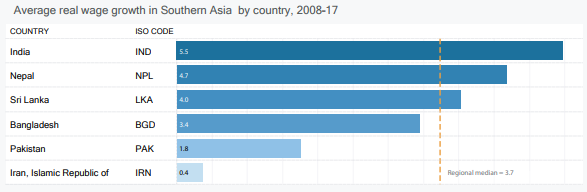

- India recorded the highest average real wage growth in South Asia during 2008–17.

- India led the average real wage growth in 2008–17 at 5.5 against a regional median of 3.7.

- Following India was Nepal (4.7), Sri Lanka (4), Bangladesh (3.4), Pakistan (1.8) and Iran (0.4).

- Workers in Asia and the Pacific have enjoyed the highest real wage growth among all regions over the period 2006–17.

- This reflects more rapid economic growth than in other regions.

- Countries such as China, India, Thailand and Vietnam are leading the way.

- All emerging G20 countries except Mexico experienced significant positive growth in average real wages between 2008 and 2017.

- Wage growth continues in Saudi Arabia, India and Indonesia, whereas in Turkey it declined to around 1% in 2017.

- South Africa and Brazil have experienced positive wage growth starting from 2016.

- This was notably after a phase of mostly zero growth during the period 2012–16, with negative growth in Brazil during 2015–16.

- Russia suffered a significant drop in wage growth in 2015, owing to the decline in oil prices.

- But since then, it has bounced back with moderate though positive wage growth.

- The U.S. posted an unchanged 0.7% wage growth and Europe (excluding Eastern Europe) stalled at about zero last year.

- Wages in developing countries are increasing more quickly than those in higher-income countries.

- Pay rose by just 0.4% during last year in advanced economies, but grew at over 4% in developing countries.

- The real wages almost tripled in the developing and emerging countries of the G20 between 1999 and 2017.

- However, in the advanced economies of G20, the increase over the same period aggregated to a far lower 9%.

- This is however seen positive in the sense of 'convergence' happening around the world.

- Nevertheless, salaries are still far too low in the developing world.

- The gaps are still significantly big as often the wage level is still not high enough for people to meet their basic needs.

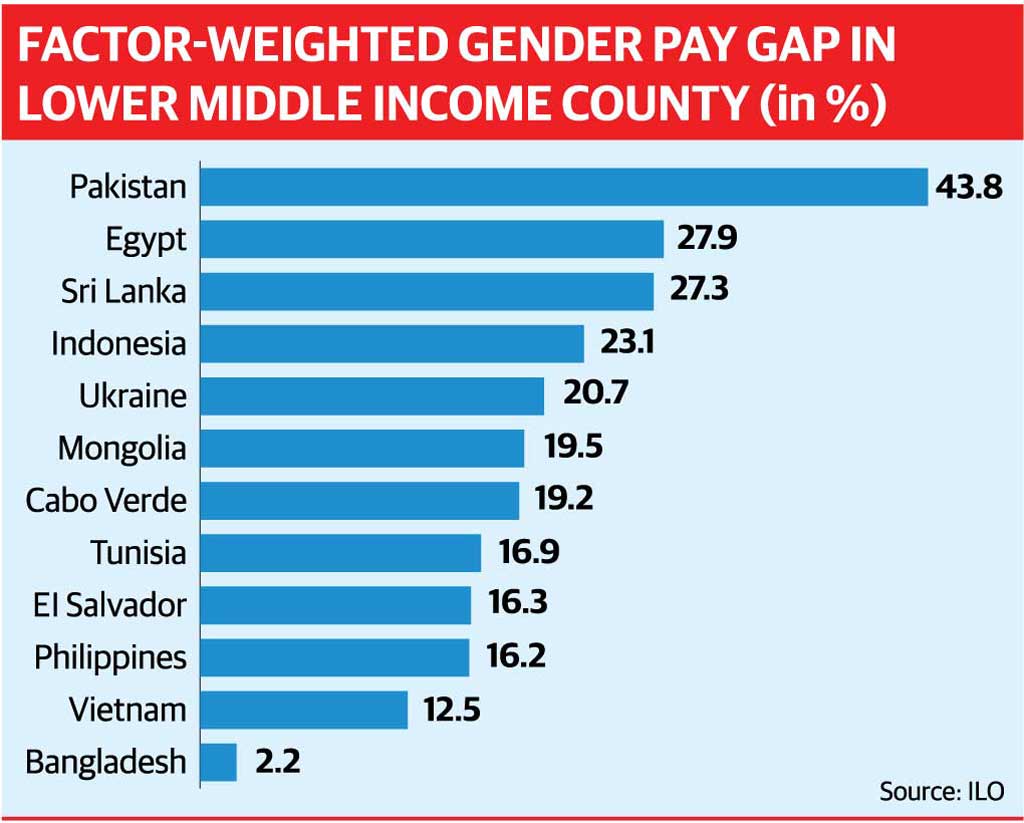

- Gender pay gap - For the first time, the ILO report also focuses on the global gender pay gap.

- It notes that despite some significant regional differences, men continue to be paid around 20% more than women.

- In high-income countries the gender pay gap is at its biggest in top-salaried positions.

- In low and middle-income countries, however, the gap is widest among lower-paid workers.

- Data suggests that traditional notions like differences in the levels of education play only a "limited" role in explaining gender pay gaps.

- In many countries women are more highly educated than men but earn lower wages, even in the same occupational categories.

- The wages of both men and women also tend to be lower in enterprises/occupations with a predominantly female workforce.

What was the driving factor for growth?

- The report noted that a number of countries have recently undertaken measures to strengthen their minimum wage.

- The prevailing view was to provide more adequate labour protection.

- South Africa announced the introduction of a national minimum wage in 2018.

- India is also considering extending the legal coverage of the current minimum wage from workers in ‘scheduled' occupations to all wage employees in the country.

What is the implication?

- It is to be noted that the overall global wage growth declined to 1.8% in 2017 from 2.4% in 2016.

- The obvious impact of this low pace of wage growth has been on global economic growth.

- It's because the consumption demand was hurt by restrained spending by wage-earners.

- So the acceleration of economic growth in high-income countries in 2017 was led mainly by higher investment spending rather than by private consumption.

- There is intensification of competition in the wake of globalisation, accompanied by a worldwide decline in the bargaining power of workers.

- This has resulted in a decoupling between wages and labour productivity.

- The effect has been the weakening share of labour compensation in GDP across many countries, which remain substantially below those of the early 1990s.

- Also, widening inequality is slowing demand and growth by shifting larger shares of income to rich households that save rather than spend.

- For India, reaping the demographic dividend needs not only jobs, but wage expansion that is robust and equitable.

Source: Economic Times, The Hindu